They have left their villages, exiled like me, though they were pushed by the economy and not by the police, and after many years they have returned to their land of origin, and they have never forgotten a thing. Not when they left, nor when they were over there, nor when they returned: they have never forgotten a thing. And now they had two memories, two countries.

In memory of Eduardo Galeano (1940-2015; El Libro de los Abrazos, 1989: 85)

One of the largest Basque cultural festivals or Jaialdi outside the European homeland is about to take place at the end of July in the peripheral-mid-sized American city of Boise, Idaho, which in previous editions has attracted thousands and thousands of people from North and South America, Europe, and as far as Australia. However, the party has already started by staging the Basque (migrant) diaspora at the center of homeland interests. It is in the context of the multi-dimensional diaspora-homeland power relationship, where the concept of “mobility” as metaphorical and physical multi-directional movement regains new meanings.

The 2010 United States (U.S.) Census indicates that there are slightly over 59,500 self-defined Basques, which compared to other diasporas (e.g., the 2010 U.S. Census reports the existence of 48 million self-defined German and 34.6 million self-defined Irish), the Basques are an extreme minority in quantitative terms. Boise’s Basque population is over 6,000 people.

Though the diaspora, which spans institutionally over thirty countries, is by far a socio-cultural or even a political reference to the nowadays Basque society, its symbolic hybridity, resilience and perdurability has become a much appreciated ideological resource for the Basque homeland hegemonic nationalism and, to a much lesser extent, for the Basque socialism. The diaspora is indeed (re)appropriated by antagonistic homeland ideologies to validate the existence of a nation, which occurs in the case of Basque nationalism, or the co-existence of different identities within an overarching political integration model with the idea of constructing an encompassing civic citizenship, which occurs in the case of the Basque socialism.

Against the backdrop of the global stage that is the United States, this symbolic appropriation of the Basque American diaspora hopes to bring attention not much to diaspora issues but to homeland socio-political issues such as the right of self-determination or the end of the anti-constitutional dispersion of ETA prisoners throughout Spanish jails. The long campaign, under the slogan of “Euskal Presoak Euskal Herrira” (Basque Prisoners to the Basque Country), which calls for the regrouping of ETA’s own “imprisoned political diaspora” in Basque jails, took a new turn on 15th of July. American personalities, including former U.S. General Attorney William Ramsey Clark, linguist Noam Chomsky, anti-war activist Cindy Sheehan, and the founder and the director of the Center of Basque Studies at the University of Nevada, Reno William A. Douglass and Joseba Zulaika, respectively, issued a declaration requesting the release of ETA prisoners as well as Arnaldo Otegi, the Basque homeland pro-independence-left movement leader. Otegi was found guilty for ETA membership and has been in prison since 2009. (ETA ended its fifty long years of “armed activity” on October 20, 2011.)

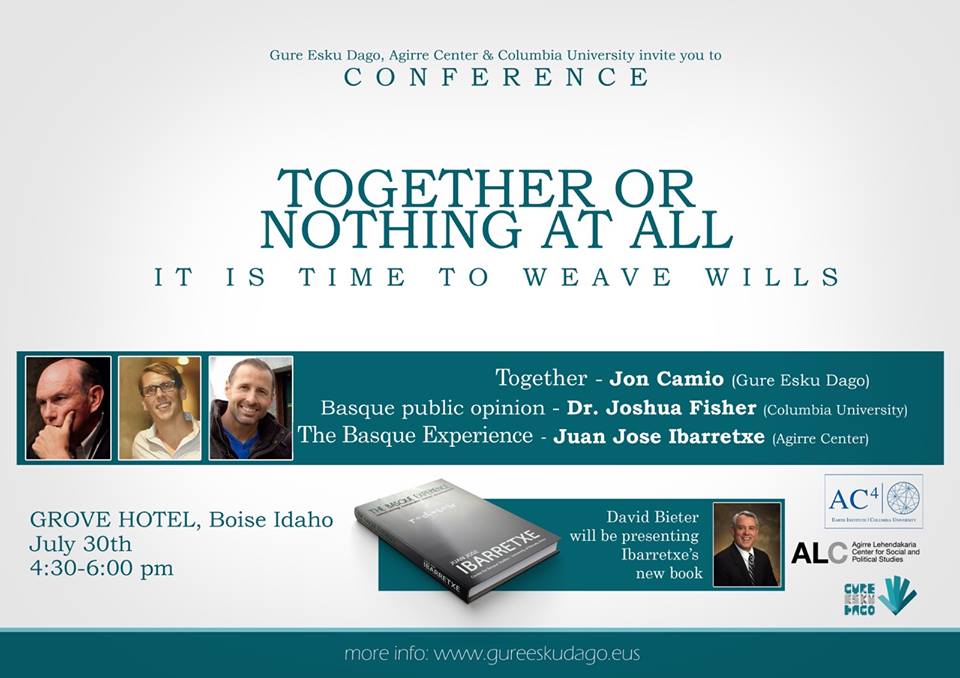

During the celebration of Jaialdi, “Gure Esku Dago” (It is in Our Hands), a Basque homeland grass root social movement that works for the right to decide the future for the Basque People, will organize with the think tank Agirre Center for Social and Political Studies and Columbia University (New York) the public conference “Together or Nothing at All. It is Time to Weave Wills.” Among the confirmed presenters are the former President of the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC) of Spain, Juan José Ibarretxe, and Basque-American Mayor of Boise, David Bieter. The potential inclusion of diasporans in the right-to-decide campaign encompasses itself a new re-definition of Basque citizenship that goes beyond homeland territoriality, and which, I presume, will not go unchallenged by some homeland stakeholders.

In addition to Ibarretxe, many other high-profile institutional figures, including the Basque President Iñigo Urkullu and the newly-elected General Deputy of the Provincial Council of Bizkaia Unai Rementeria, and political parties’ representatives will also visit Boise on an official trip to the U.S. President Urkullu will host a reception on July 31st. Not-coincidentally this is the day of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, i.e., the Patron Saint of the provinces of Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa as well as the Boise Basque Catholic community.

On the other hand, on a less publicized way, a group of about sixty migrant returnees and their family members, mostly from the province of Navarre, will tour the American West under the auspices of the homeland association “Euskal Artzainak Ameriketan” (Basque Shepherds in America). For many of them, this will be their first visit after decades since their permanent return to the Basque Country. The group will arrive at Boise on the 30th. For over two weeks they will revisit their old places of work and residence, while reencountering lost friends and forgotten memories. It evokes the story of endless returns and back and forths, which lay in the origins of the sojourned Basque diaspora in the U.S. since the mid-19th century. The majority of the young Basque men from France and Spain who came to America worked in the sheep industry as herders and camp tenders, most of which returned to Europe after years of intensive manual labor work.

Moreover, five charter flights filled with Basque homeland tourists will reach at one point or another the Boise festival as a new commodified tourist destination. This brings a new perspective into the “back to the roots” (tourist) phenomenon, where diasporans visit the land of their ancestors as an attempt to discover their past or to reconnect with it. As we can see here the reverse situation is also true. Indeed, mobility, in the particular case of Basque America, is constantly redefined, while making visible other types of movements of people. For Basques the migration circle remains open, connecting many memories and many countries.

The time has come for the Basque world to turn its eyes to its diaspora in the United States. Taking into account that nearly 70% of the population of the BAC had never had any direct experience with the Basque diaspora, Jaialdi might be a great opportunity for homeland visitors and alike to increase their knowledge about diaspora Basques, their cultures and the different means of being Basque. It would also be a perfect occasion not only to acknowledge their contribution to the common past and present that Basques shared across the globe, but to rethink how diaspora Basques could relate to the homeland in a more inclusive and participatory way.

Lagun bati bidali

Lagun bati bidali Komentarioa gehitu

Komentarioa gehitu