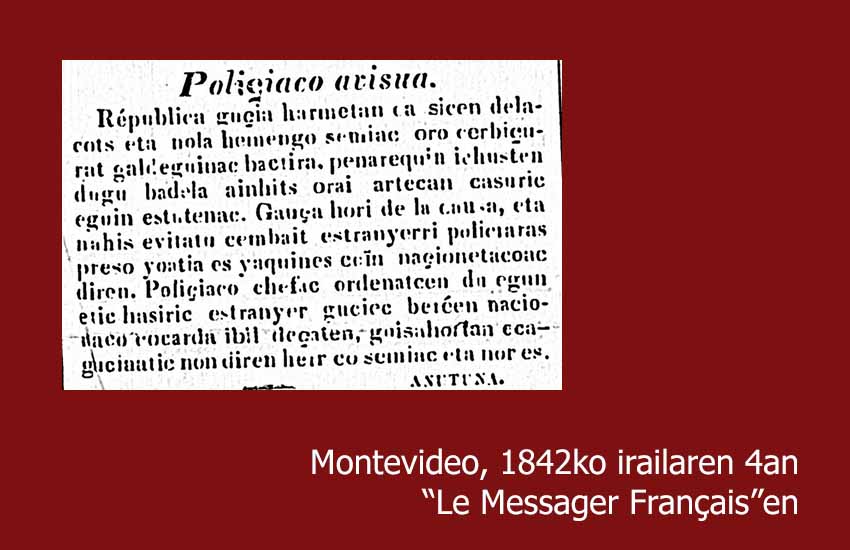

Xabier Irujo and Alberto Irigoyen. The note was inserted don the first page of the daily Le Messager Français (The French Messenger) on Sunday September 4, 1842, and is probably the first notice written in Euskera in an American Press. 178 years ago.

The situation was desperate. In the context of the Great War (1839-1851), the Colorados led by Fructuoso Rivera expected the attack of the Blancos led by Manuel Oribe, allies of the Argentine Federals led by Juan M. Rosas. Oribe had not yet besieged Montevideo but the city was preparing for the invasion and the authorities called for the compulsory conscription, from which foreigners were obviously exempt. The text in Basque, signed by the political and police chief of Montevideo José Antuña, explains that the Republic was taking up arms and that, despite the fact that all men had been called up to fulfill their military duties, it had been sadly observed that many had ignored the order. The chief of police thus ordered to arrest the nationals who refused to enroll and instructed that the foreigners, among them a large number of Basques, should wear a visible cockade (know of ribbons) with the colors of their home country to avoid being arrested as nationals.

Poliςiaco avisua

Républica guςia harmetan [c]a[u]sicen delacots

eta nola hemengo semiac oro cerbiçurat

galdeguinac bactira, penarequin ichusten

dugu badela ainhits orai artecan casuric

eguin estutenac. Gauςa hori dela cau[s]a,

eta nahis evitatu cembait estranyerri policiara[t]

preso yoatia es yaquines cein naçionetacoac

diren. Poliςiaco chefac ordenatcen du egunetic

hasiric estranyer guciec bereen nacionaco

cocarda ibil deçaten, guisa hortan ecaguciaatic

no[r] diren heirco semiac eta nor es.

[Antuña]

Various linguistic elements of the text suggest that it is a note written by a Basque speaker from Iparralde, the northern part of the country. For example, the author calls the chief of police “chefa” (from the French, ‘chef’), and the use of the adverb “ainhits” or the noun “estranyerri” are also typical of northern speakers of the language. The adverb “orai” is used mainly in the Northern Basque Country, while in Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa the form “orain” is preferred, however, “orai” is also recorded among speakers from the north-west of Upper Navarre in Hegoalde, the Southern Basque Country. In general, the majority of the Basques of Uruguay in the first third of the 19th century came from Iparralde, although from 1839 the number of exiles and emigrants from Hegoalde increased notably.

In a city where the majority of the population were foreign immigrants, both the consular representatives and the government authorities agreed that the defense of Montevideo was only possible if foreigners were recruited. Shortly after this press note was released, the Spanish immigrants from the Canary Islands were withdrawn from their status as foreigners and enrolled. The Italian and French legions were soon created, but despite Jean Thiebaut’s efforts to attract the Basques into his French unit, the majority of them did not want to enlist. As a consequence, with special attention to the Basques, an announcement was published in Basque in Le Patriote Française in 1843, which informed that the foreigners who fought in defense of the city would be granted land and farm animals after the war in payment for their gallantry. The Basques would fight in Basque units under Basque command. Only then did they voluntarily enroll. The government appointed Juan Bautista Brie de Laustan, a native of Donibane Garazi, as colonel of the newly formed Battalion of Basque Hunters or, Chasseurs Basques. Initially, this battalion had 659 troops and maintained an average of 600 troops throughout the war.

Oribe’s troops also had a Basque unit, the Oribe Volunteers battalion whose colonel was Ramón B. Artagabeitia Urioste, a native Santurtzi (Bizkaia.) The number of volunteers in this unit rose to 689 men and their camp was known as “Oribe Erri” (‘Oribe’s town’ in Basque.) Some of them were former Carlist soldiers, from Hegoalde, who had fought for seven years (1833-1839) in the worst conditions and who had managed to challenge the Spanish government’s troops that were finally forced to sign a peace agreement in Bergara in 1839. Their fame preceded them and given the need for men-at-arms, their Basque origin was recognized, their right to serve only in Basque battalions under Basque command and they were even recognized the ranks they had held and their salaries during the First Carlist War or the War of the Seven Years (1833-1839).

This way, from 1842 on, those who had fought in the Basque Country were once again involved in a warlike conflict that confronted them on two different sides. The siege of the city, which started in February 1843, lasted more than eight years, until October 8, 1851.

Until now, it had been argued that the first text in Basque ever published in an American newspaper was the aforementioned article published in May 1843 in Le Patriote Français in Montevideo, but obviously this one was published before. It is undoubtedly one of the first texts written entirely in Basque in an American newspaper. It is believed that the history of modern journalism in South America begins with the appearance in Peru of the Diario Erudito, Económico y Comercial de Lima in 1790. In 1807, the first issue of the Estrella de Sur was published, which sparked the beginning of journalism in the south and La Gaceta de Montevideo was first printed in 1810. We still need to keep looking in the archives of an entire continent, but so far, this is the oldest note written in Basque in an American newspaper that we have found.

As a curiosity, in the issue of Le Messager Français of September 13th, we found an ad from a person, of impeccable morals, who was looking for a job as a coachman or in the construction sector and who spoke French, Spanish, and Basque. In the October first issue, another ad was inserted in which a young man who spoke French, Spanish, and Basque and wrote correctly in all three languages, offered himself to work in a trading house “dealing with correspondence in the three languages,” which indicates that Basque was used as a language for commercial transactions in the city.

Send to a friend

Send to a friend Add comment

Add comment