Pedro J. Oiarzabal. On August 27, 2020, some players from the NBA, followed by professional baseball and football players, boycotted the games they were to play in response to the death of Jacob Blake, an African American who was shot by a white police officer in Kenosha, Wisconsin on August 24th. This episode added to the long list of incidents of police brutality and racial injustice that gave rise to the Black Lives Matter protest movement across the United States in 2020. The political stance of these players against systemic racism was even more shocking, but if it fits an extremely tense and polarized society, particularly since the arrival of Donald Trump to the presidency of a country a little over four years ago.

That same day, Rafael Anchia Michelena, member of the Texas State House of Representatives for the Democratic Party since 2005, expressed his support for the decision taken by the NBA players. He wrote on his Twitter account: “My father was a professional athlete, who joined the union and went on strike in 1968. He was fired and blacklisted and his Jai Alai career ended at its best. However, he defended what he thought was right.”

The traditional narrative built on the world of Basque pilota, and especially on Jai Alai on American soil, rarely considers them, as it does with the famous Basque shepherds in the American West, as migrant workers, subject to rights and obligations. In itself, both the pilotari and the sheepherder are romanticized to such an extent that often the fact that they are workers is consciously diluted. The author of these lines was interested in the perspective of today’s state congressional representative, Rafael Anchia, who had undoubtedly known the situation firsthand through his father, Julio Anchia Garechana. After contacting his collaborators, we arranged an interview that took place on September 15th.

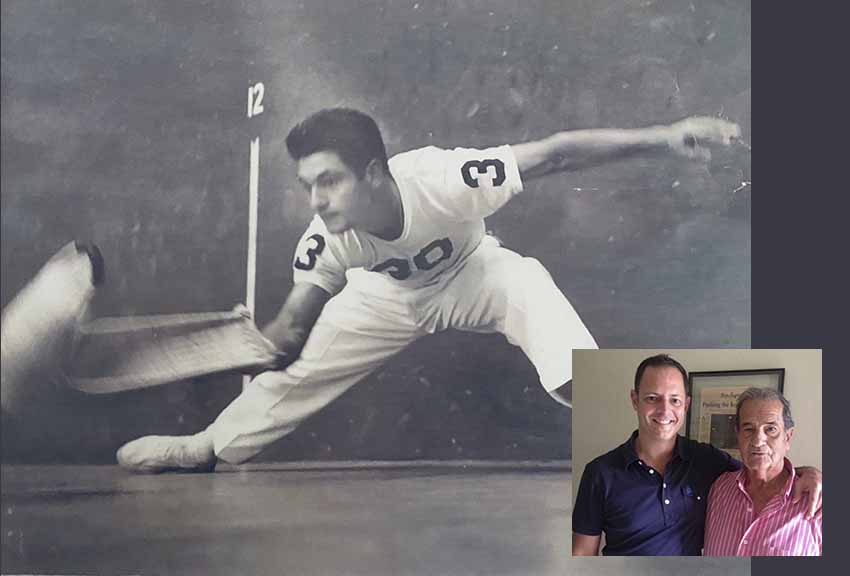

“My father defended what he thought was right” (courtesy of the Anchia Family)

We spoke for an hour about his father’s career in the world of pelota, its significance for a Basque family in the postwar period, his professional career, and the consequences of supporting a labor strike that ended his career.

Julio Anchia Garechana was born on December 4, 1936 on the way to the Longa Farmhouse in Mallabia, Bizkaia, nearly five months after the start of the Spanish Civil War. When he was 15, he began his career as a professional Jai Alai plyer in Zaragoza, Spain, where he would leave two years later to go to Naples, Italy, realizing, finally the dream of all pelotaris to cross the Atlantic and play in the United States. And so, in 1955, he arrived in New York at the age of 19, and began playing in Dania, Florida. It was the golden age of Jai Alai. The ball courts or frontons in Dania and Tampa had been inaugurated in 1953, and another one in West Palm Beach in 1955. The fronton in Daytona would open its doors in 1959, and the one in Orlando in 1962. In a few years, Julio would become an excellent player.

Image 1. A young Julio Anchía posing with his chistera (photo https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Julio_Anchia.jpg)

Image 2. Jai Alai players at the Dania Jai Alai Palace in Florida during the 1955-1956 season. Julio Anchía is number 12, in the third row, fourth from the left (courtesy of the Anchia Family).

After being recognized as the “rookie of the year,” in Dania, Julio joined in the organized activities for players in 1956, where they sought benefits, and basic rights. Faced with the reluctance of the companies that managed the frontons, and “for going on strike,” Rafael clarifies, “my father was blacklisted and was forced to leave the country, losing his career and immigration status. He was forced to leave the country for Mexico and there he would play at the fronton in Tijuana.”

Upon his return, he would continue his professional career in Miami and Daytona. In 1962, at the age of 31 and with 15 years as a professional, he confessed to The Miami News, “I am ready for another 15 years. You only come into your prime in Jai Alai after 10 years.” (2). In 1967, he married Edurne Michelena, born in Mexico City and educated at the University of Barcelona, whose father, Justino Michelena, had been a pelotari having been exiled to Mexico as a result of the war in Spain. A year later, Rafael was born in Miami. However, the future would not be flattering at all. After the cend of the 1968 season, players, including Julio, demanded better working conditions to the companies (increased wages, better health insurance, etc.) or they would not play in the coming season. Meanwhile, pelotaris, as foreign workers and linked to a temporary work visa, had to return to the Basque Country. The owners of the companies rejected all of their proposals, threatened not to renew their visas, and finally began to replace any player who did not want to remain linked to the company with players with less experience and cache. “Support of the strike meant the end of my father’s career,” says Rafael.

After returning to Markina, the young couple, and small son, had to remake their lives. His father’s dream was cut short by the strike. “Pelota,” remembered Rafael, “had given him everything and took everything away.” It was a traumatic experience. He didn’t even talk about the golden years of pilota. He didn’t even see matches.” Without a formal education, nor command of English, Julio was obliged to do all kinds of work in Miami, including door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesman, while his mother began her own career in the world of education as a teacher.

In time, Julio would return to pilota. He first managed amateur canchas in South Miami, Amateur Jai Alai and Orbea’s Jai Alai, and later he would enter the profession of making the cestas and balls, where he would work for the rest of his life. Julio retired at the Dania Beach Jai Alai as a ball maker in 2006, at the age of 69.

Julio Anchia sews a ball for the Dania Beach Fronton in his last year as a ball maker (Florida Today, January 23,2006)

Julio’s story, like that of so many other pelotaris, is a story of overcoming the tragedy that occurred, which forced them to leave at the zenith of their profession renouncing their rights as workers. They are the stories of yesterday and today in an America that fails to overcome its deep inequality and its racial divisions. “My father understood the importance of educational opportunities to overcome difficulties, regardless of the sacrifices made, so that they could increase my chances in life,” Rafael says. In fact, Rafael, a pelotari since the age of 4, was selected by the United States to make his debut in the 1986 World Pelota Championships, celebrated in Vitoria-Gasteiz. Faced with his father’s reluctance and the offer of a scholarships to study at the Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, Rafael chose to follow his father’s advice which meant the end of his career as a pelota player. The subsequent Jai Alai strike in 1988, ratified his decision. His teammates were out of work.

Rafael Anchía with his sister Christina and his parents Julio and Edurne in Miami in March 2016 (courtesy of the Anchia Family)

In the meantime, let’s go back to the Basque Country to the current date, at a time when the fifteen pelota players of the Baiko Company started a series of strikes affecting the official competitions on October 6th. Twenty-one days later, they reached an agreement with the League of handball Companies that granted most of their demands, including a minimum gross annual wage and the payment of travel stipends. At the same time, the first association of pilotaris was formed in defense of their labor interests. Everyone won.

On the contrary, three decades earlier, the strike carried out by Jai Alai players in the United States from 1988 to 1991, broke the sad record of being the longest in American professional sports. Until the last minute, the companies did not even recognize neither the right association of the Jai Alai players nor the International Jai Alai Players Association (IJAPA), supported by most players. It was another time and another country, and despite a favorable resolution for the players, Jai Alai was never the same again nether as a sport or as a business. It was an all-or-nothing game in which everyone lost (1).

Let’s look to the future, being very aware of the sociopolitical situation in the United States, embroiled in a war of ideological trenches that seems to have no easy solution. “We all have a past, and we must try to build the present that we want our children to inherit,” Rafael concludes. The game continues.

(1) Abrisketa González, Olatz. “A Basque-American Deep Game: The Political Economy of Ethnicity and Jai-Alai in the USA”, Studia Iberica et Americana, Year 4, Issue 4 (December 2007): 179-98. The Miami News. February 17, 1962. P. 16.

(2) The Miami News. February 17,1962. P. 16.

Send to a friend

Send to a friend Add comment

Add comment